Frege's Values

Frege’s Values

By Greg Langmead, December 2021.

In the final decades of the 19th century Gottlob Frege expanded the power of logic as well as its scope. His stated goal was to show that the natural numbers could be created inside logic. But why was he doing this? What benefits did he think this would have and what value statements did he provide? I will show that what Frege valued was the rigorous pursuit of mathematical truth, and that he viewed his own contributions as entirely methodological. I will further show that this view, that logic serves the broader mathematical endeavor, is consistent with major streams of foundational mathematical activity today. I will examine type theory and the communities who use it to cultivate a flourishing mathematical practice. But lurking inside this rosy picture is a new crisis for mathematics. Ironically, this is not another instance of the crises of the 19th and 20th centuries, where mathematics required a renewed commitment to rigor in order to avoid confusion, paradoxes, or errors. There are indeed vocal elements today who claim that we are in just such a crisis! But this time we have all the tools we need to achieve the desired standards. Unfortunately, the proponents of those very tools have indirectly brought about a crisis of values, by supporting and celebrating a nihilistic, computational, and literally dehumanizing view of mathematics. What we need now is to repel these attacks with a new commitment to Frege’s values: that logic is a tool of the inherently human exploration of mathematics, and not a value unto itself.

Table of Contents

1. Frege’s goals: logic in service of mainstream mathematics

Frege’s first big document, the Begriffsschrift (1879), begins its preface with the sentence “The recognition of a scientific truth generally passes through several stages of certainty.”1 The rest of the document, and indeed Frege’s entire body of work, is devoted to upgrading the certainty of scientific truth. The value is truth, and his methodology would help lend additional certainty to it. He does not level any criticisms at the agenda inside of mathematics or science generally. It’s true that he argues for what we would call a realist take on science and mathematics, i.e. the position that mathematical objects are real objects in a platonic realm of ideas. It’s also true that he argues against a psychological frame for such objects. But these are philosophical underpinnings, and again do not second guess the activities that the practitioners choose to focus on. So the arc of scientific inquiry, and of mathematical research, is a fixed background object that he seems to approve of and wants to support.

The support he wants to offer is an epistemological upgrade: more airtight arguments which are more grounded in logic. Delivering this upgrade has two parts. First Frege will add constructions to logic itself, notably universal quantifiers, a primitive system of types, and the observation that equality comes in multiple kinds. This enables the logic to support a broader class of reasoning.

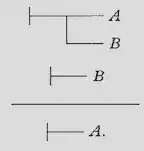

With his suite of logical tools, Frege can offer his second idea, which is the Begriffsschrift, or concept script, itself. This is a notational tool for a mathematician to apply the laws of logic to some starting expressions that have been suitably encoded, working down the page applying laws of inference from the small permitted library, until a conclusion is reached. It is crucial that the concept script is a new notation, with little in common with spoken and written human languages except the use of letters for variables (he cites “the inadequacy of language”2). Here is an example that in modern notation would be “B ∧ (B → A) → A” or in words “if B holds, and B implies A, then A holds”3:

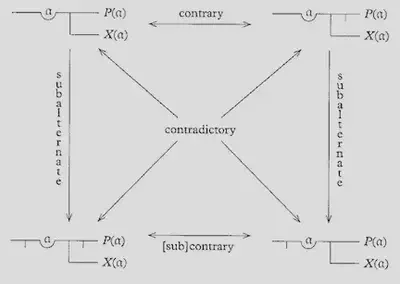

and here is his diagram showing that his expressions can subsume the “square of opposition”, a sort of ad-hoc logical tool used over the preceding centuries45:

Frege’s proposal can be expressed as a layer diagram, where lower levels support the ones above, and higher layers make use of the ones directly underneath:

Science and Mathematics

-----------------------

Concept script

-----------------------

Logic

He wanted the concept script and logical framework to be adopted, to be used by mathematicians in daily practice, or at least when extra certainty was desired. The concept script is the interface to the logic, and so if a practitioner were to successfully use the concept script to prove a result, that result would be connected all the way to the logical bedrock of knowledge:

The firmest proof is obviously the purely logical, which, prescinding from [i.e., holding itself apart from] the particularity of things, is based solely on the laws on which all knowledge rests.6

The user is empowered to avoid all intuitive leaps; the proof would be free of gaps:

So that nothing intuitive could intrude here unnoticed, everything had to depend on the chain of inference being free of gaps.7

Everything that is necessary for a valid inference is fully expressed [in the concept script]; but what is not necessary is mostly not even indicated; nothing is left to guessing.8

His comparison of the concept script to a microscope is very illuminating. First of all it is a tool which we use to examine the true subject matter at hand, namely scientific truth. But used properly the microscope does not set the agenda or ask the questions. It is a tool that lays alongside the primary inquiry.

He even includes a roadmap of future goals for the concept script, to support even more scientific areas such as geometry, analysis, and physics:

It seems to me to be even easier to extend the domain of this formula language to geometry. Only a few more symbols would have to be added for the intuitive relations that occur here. In this way one would obtain a kind of analysis situs. The transition to the pure theory of motion and thence to mechanics and physics might follow here.9

The analogy to a software library gaining features over time is hard to avoid, and I don’t think it needs to be avoided! But the point I want to keep emphasizing is that he is not trying to disturb the trajectory of these fields, he’s trying to help them succeed. The scientific fields in question already have the right mission statements: scientific truth. He is aligned with that goal.

Frege might feel that I am downplaying his primary achievement, which was to enlarge logic to the point where the natural numbers and laws of arithmetic were included directly in the logical layer. This was the subject of his later works The Foundations of Arithmetic (1884) and Basic Laws of Arithmetic (part 1 in 1893, part 2 in 1903). Since the real numbers had been built up rigorously from the natural numbers by contemporaries such as Richard Dedekind, Frege would be connecting the whole edifice directly into logic. He felt this was a big missing piece:

Yet is it not shameful that a science should be so unclear about its most prominent object, which is apparently so simple?10

He spends many pages of these later works trying to define “concepts” and “objects”, so that numbers can be given the status of real objects in a platonic sense. He captures his definition using something similar to set theory except that the atomic objects are extensions of concepts. Concepts in turn are propositional functions, that is functions that have the value True or False for any given object. The extension of the concept is then all the objects that yield the value True when plugged into the function. Then he defines 0 and 1 and a successor function, and can then use the concept script to prove theorems about arithmetic.

This part of his quest, subsuming arithmetic into logic, is not easy to assess. Most of it in The Foundations of Arithmetic takes the form of philosophical writing in human language, like any other philosophy paper, and so it’s doubtful he has an airtight case. But it doesn’t matter so long as we allow ourselves to deal separately with the philosophical status of our foundations, and the inferences we make from those foundations. The successful portion of Frege’s work is the strategy of building a system of logic, and then somehow empowering ourselves to make airtight arguments starting from that system. Frege himself does just this in the subsequent Basic Laws of Arithmetic, wielding his concept script to prove the laws of arithmetic starting from his definition of the natural numbers.

Tying it all together we have these elements:

- Science and mathematics have value.

- They generate value in part because they are rigorous.

- Enhancing the rigor would enhance the power and the value of these activities.

- The enhancement can be brought about by expanding logic and by creating methods to effectively wield the logic: tools for people to perform gap-free inference.

2. Formalizing mathematics: carrying out Frege’s project

The microscope that Frege invented is a logical system with a primitive notion of types. The type system consisted of “objects” at the lowest level, then functions of objects at level 1, then higher functions at the higher levels. His logical rules of inference are these nine (in modern notation):

- ⊢ a → (b → a)

- ⊢ (c → (b → a)) → (c → b) → (c → a)

- ⊢ (d → (b → a)) → b → (d → a)

- ⊢ (b → a) → (¬a → ¬b)

- ⊢ ¬¬a → a

- ⊢ a → ¬¬a

- ⊢ (c ≣ d) → f(c) → f(d)

- ⊢ c ≣ c

- ⊢ ∀a.f(a) → f(c)

Quite a lot of his specification is easily recognizable today, of course because we adopted it. His introduction of the universal quantifier, for example, (∀ in modern notation) was an original and impactful contribution. He was also careful about the use of bound and free variables in the concept script, and of the fact that the quantifiers need to have their scope specified. He also distinguished two kinds of equality to accompany his two levels of meaning, known as sense and reference. The sense of an expression is the exact meaning of the syntactic encoding (but isn’t the same as the syntactic encoding itself, which is a distinct third layer we can ignore here), and the reference is a semantic object to which the sense eventually refers, possibly after doing a lot of work to unpack the sense. His famous linguistic example is how “the morning star” has the same reference as “the evening star” since both are the planet Venus. But they differ at the level of sense, and they pick out the planet via different methods. Similarly, the equation “a = a” holds because the senses are syntactically the same, whereas “a + b = b + a” holds after a short proof, i.e. the senses differ but the references turn out to be the same. All of these ideas remain relevant today and we’ll return to them when we look at type theory.

It’s not just the logic that was prescient, but the concept script as well. Compare the concept script notation we saw earlier with, say, the heavy use of prose in most mathematics textbooks from the last 150 years. Most mathematicians are content with a lesser version of rigor, where arguments are made very carefully and as airtight as possible, but remain optimistically rooted in the intuition and incisiveness of the human operator. Frege did not think this was good enough:

The requirements on the rigour of proofs inevitably result in greater length. Anyone who does not bear this in mind will indeed be surprised at how long-winded the proof often is here of a proposition that he believes can be immediately grasped in a single act of understanding. This will be particularly striking if we compare Dedekind’s work Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?, the most thorough work on the foundation of arithmetic that has come to my attention in the last few years. In much less space it pursues the laws of arithmetic much further than is done here. This brevity is admittedly only achieved by not really proving much at all.11

Patrick Massot, a prominent member of the Lean and Mathlib community, makes a convincing case12 that it is easy to overlook special cases such as the empty set when reasoning informally, but that Frege-style gap-free reasoning, of a kind that is literally being performed today with the help of computers, will catch these cases. This sort of completeness of argumentation is helpful, even crucial, and Frege deserves credit for focusing on this part of the challenge. Frege was clearly able to relate to the experience Massot is describing, where the formal system informs the operator that they must consider the case of the empty set:

one must write down all intermediate steps, to let the full light of consciousness fall upon them.13

I’ll have more to say about computers and Mathlib shortly. But before I leave the subject of computers for now, it’s important to note something we do not see in Frege’s value system. There is a danger of conflating strictly computational activity, such as that performed by digital or human computers with mindless or degrading or even harmful jobs14. There is no evidence that Frege felt this way about a would-be operator of the concept script. We have just seen that he admitted the proofs would be long, but nowhere does he mention automation or machinery. He seems to have envisioned even the fully rigorous process as intended not only for people, but for mathematicians themselves.

3. Disagreement with Hilbert

I want to discuss something Frege knew about but wrongly rejected. It’s a little depressing that he missed out on it, because as we will see it’s the other piece of the modern point of view, and enabled the vindication of Frege’s logic and concept script in the end.

In 1899 Hilbert published Foundations of Geometry, which we recognize now as a major development. He proposed splitting mathematical theories, such as Euclidean geometry, into two parts. One part contains the axioms of the theory, including any conceptual objects which the theory will talk about and operate on. For geometry the objects are points, lines, line segments, circles, angles, and so on. The axioms could be, say, Euclid’s postulates (from Wolfram MathWorld15):

- A straight line segment can be drawn joining any two points.

- Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line.

- Given any straight line segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center.

- All right angles are congruent.

- Given any straight line and a point not on it, there exists one and only one straight line which passes" through that point and never intersects the first line, no matter how far they are extended.

The second part of the theory is to take the axioms and interpret them in some specific mathematical setting. We could interpret all the objects (points, lines, etc.) in the usual Euclidean way in the plane, for example. But we could also work on a two-dimensional sphere and interpret “point” to mean “pair of antipodal points on the sphere” and “line” to mean “great circle”. We then get a second consistent theory except for postulate 5, which fails to hold because instead of having one such line, there are none.

There are at least three things going on here. First of all, it condenses geometry, both Euclidean and non-Euclidean, into a concise logical package. Secondly it empowers us to split our arguments into two parts. One part can focus on all the deductions we can make inside the system, simply based on the axioms, without referring to the interpretation. Some results require postulate 5 for their proof and these hold only in the planar interpretation. I like to think of the purely axiom-derived theorems as supplying strong answers to “why” questions. Why does some fact hold in both Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry? If we can prove it straight from the postulates, then it is because anything that obeys postulates 1-4 also obeys this rule. In a way the axiom systems together with deductions therefrom constitute a schema for a whole family of mathematical theorems.

But Hilbert’s method also gives us one more capability. We can directly ask whether the axioms are consistent, or the related question whether some of the axioms are independent of the rest. Since there are two interpretations of postulates 1-4 one of which obeys postulate 5 and one of which does not, we can conclude that postulate 5 does not follow from 1-4. That’s a result that took 2,000 years to discover. By moving back and forth between the axioms and some clever special models, we can conclude things just about the axioms. The independence of axiom 5 follows from an argument that uses a model. This is a standard trick today, which is why this was a major development.

When I learned that Frege responded strongly against this idea of Hilbert’s, I was truly surprised. What were his objections? Frege wrote:

No man can serve two masters. One cannot serve both truth and untruth. If Euclidean geometry is true, then non-Euclidean geometry is false, and if non-Euclidean geometry is true, then Euclidean geometry is false.16

If one is content to have only phantoms hovering around one, there is no need to take the matter so seriously; but in science we are subject to the necessity of seeking after truth.17

The “phantoms” would presumably be the bare axiom system, devoid of interpretation.

It seems clear Frege is misunderstanding Hilbert, but I think we can learn some important lessons even from that. The misunderstanding is that Frege is unable to, or unaware that he should, merely postpone the interpretation of the axioms. The phantoms are temporary, and the process definitely has two steps. Frege insists in the first quote that the axioms must be true which entails that they also be fully interpreted. He and many other thinkers believed they were being invited to live only in axiom-space, proving empty results with no meaning. This was likened (pejoratively) to a game, and is given the name “formalism”. Hilbert retorted in 1919:

We are not speaking here of arbitrariness in any sense. Mathematics is not like a game whose tasks are determined by arbitrarily stipulated rules. Rather, it is a conceptual system possessing internal necessity that can only be so and by no means otherwise.18

I would argue that Frege is doing more than simply misunderstanding the proposal. He is defending mathematics from being drained of meaning. Hilbert is not of course draining it of meaning, but Frege thought he was and it bothered him. A geometrical point is a mathematical object and claims about it can be true or false, and such claims have value. An axiom is just a phantom, and has no value at all. This is very clarifying for us. If we consider Hilbert’s procedure a piece of new technology, Frege is like a luddite, worrying whether it will damage the field of mathematics.

Frege must have believed this so fully that he did not take advantage of the synergy with his life’s work. The combination of axioms with logic allows an even larger portion of mathematical proofs to remain analytic, rigorous, and also general. The original theorems in planar geometry are fully recovered after performing interpretation, so nothing is lost but many new theorems are gained simultaneously, across all known and future interpretations.

In hindsight, Frege was trying to base his theory of natural numbers directly in platonic philosophical bedrock. He spent many pages arguing philosophically about concepts, functions, and extensions of functions, to lend credence that numbers are real objects. This is the realist part of his philosophy, but it’s actually not dependent on, or coupled to, the logical tools. We can preserve the logic and the value system, the quest for mathematical truth, and plug these into Hilbert’s axiomatic approach instead of into would-be real objects. In fact maybe we can even preserve the realism! Frege could have blessed certain interpretations of the axioms as “real” for example. But this counterfactual will not be of use to us here.

4. Modern foundations: vindication of Frege’s logic

4.1. Synthesis of Frege and Hilbert

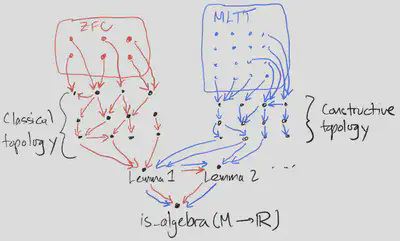

Here is a very informal picture of modern mathematical foundations: mathematics is a graph structure (see picture below). It’s not a true formal graph, but the metaphor is so close to true that perhaps it could be made precise even without an explicit formalization like the ones we will discuss shortly. Each node is a theorem, and the edges (which are directed) represent the interdependency between the theorems. In other words, each node has a proof that makes use of the incoming edges. Maybe there are multiple proofs, each of which draws on a different subset of the edges. The source nodes, those with no incoming edges, are either axioms or definitions. The leaf nodes, with no outgoing edges, are results that are not yet used to prove something else. Some of these are at the frontier of research, and might be extended one day with outgoing edges to new results.

Let’s fix our attention on some node, such as the theorem which states that the collection of smooth functions {f : M → ℝ | is_smooth(f)} forms an algebra under pointwise multiplication and addition, and multiplication by real numbers. Call this node “is_algebra(M → ℝ)”. Now light up all the nodes that lie on some path that flows into is_algebra(M → ℝ). If we are working in a foundation system like ZFC, then there are some ZFC axiom nodes, and also some definition nodes from various theories that we need (such as topology and calculus). From these there are edges that flow through a bunch of intermediate nodes (lemmas and other theorems) into is_algebra(M → ℝ). For example, somewhere there is a node that states that the pointwise product fg of two smooth functions f, g : M → ℝ is itself smooth. This will be needed to show that the algebra is closed under this operation.

This can all be formalized in a computer program (perhaps a proof assistant) that offers a system of logic together with the ZFC axioms. We then have some really valuable outputs: we have is_algebra(M → ℝ) itself, plus some documentation about the proof. But note that it’s relative to a few things:

- The choice of ZFC as our foundations

- The choice of logical system

- The computer software, for example Metamath19

Hopefully the computer program doesn’t add very much on top of ZFC and the logical system, but it’s always possible there are bugs or other caveats hiding in there, so we’d better include it. We might be using a different proof assistant such as Lean, which uses a form of Martin-Löf type theory (MLTT) and which in general supports only constructive logic (though I hasten to add that you can add extra axioms that permit classical reasoning such as the law of excluded middle, in which case the results are simply applicable to fewer interpretations, in the Hilbert sense, of MLTT.)

This relativism is a part of the modern picture of mathematics that I want to highlight so we can compare it with Frege’s ideas. Mathematicians themselves explore the relativism inside of mathematics, by swapping in various axiom systems and various logical systems, and re-proving the theorems. Some mathematicians practice reverse mathematics20 which is a project to explore the entire graph I described, for example by discovering requirements for some given axiom system to support (flow to) some family of theorems. Software practitioners that use multiple computer software packages in fact must move between foundations, since with our current technology they are forced to reimplement theorems in each programming language separately, and those languages may also have different logics. There is a large body of Coq software, and a separate body of Lean software as well that covers an overlapping set of theorems, and similar bodies of software in other languages.

Frege acknowledged that there may be imperfections in his logical axioms and inference rules. In fact he was made aware of a paradox by Bertrand Russell and tried to repair it. But he doesn’t indicate that we should entertain having more than one such system. It’s nearly certain that his views were incompatible with such a notion. As we saw, he tried in true realist fashion to ground his logic in philosophical bedrock, in order to increase the world’s total number of true, realist, complete logics from zero to one. His aversion to Hilbert’s rootless vision of axiom systems is another hint that there was room for only one version of the truth. We can’t rule out that he could have made room for multiple foundational vantage points, of course. Setting that difference aside, the narrative that begins after we select a foundation is very much compatible with Frege: we use the foundation to prove the same family of theorems, on the same quest for scientific truth, and establish them firmly and free of gaps.

4.2. Type theory

The particular foundation offered by Martin-Löf’s intuitionistic type theory2122 is especially noteworthy in this context, since it so perfectly incorporates the Hilbert picture into the foundations, while also capturing all three of Frege’s most important contributions that I am highlighting: logic, a system of types, and two kinds of equality. In intuitionistic type theory the types are “Hilbertian”, meaning they are abstract objects that are meant to eventually be interpreted into more concrete mathematical objects. And the interpretation process is completely formal and mathematical! For example if a mathematician has some objects of interest to which they wish to apply type theory (such as sets, or sheaves of sets over a topological space, or many other examples), they simply have to arrange for those objects to live inside a category with a few specific properties and the type theory will automatically be interpretable on these objects. Proofs expressed in type theory become proofs about those objects. Different versions of type theory with more or fewer features will require different features to be present in the category. That rather beautiful picture covers the Hilbert side of things.

On the Frege side, intuitionistic type theory has his notion of function objects and his distinction between free and bound variables, and the requirement that variables have types. It’s definitely more fleshed out and carefully thought through than what Frege gave us, but I believe it fulfills the very requirements that Frege set out.

Miraculously, in type theory the logical framework is actually emergent from the type system! This is in some sense the greatest validation of Frege of all. Just by having function types, product types, coproduct types and so on, and assigning universal properties to these, we do not need to separately impose a logic. The behavior of the function types, for example, automatically establishes that B ∧ (B → A) → A. The behavior of the product types satisfies the rules of conjunction, and the coproduct types do the same for disjunction. Type theorists call this emergent logic “internal” since it uses the material of the types to state and prove results. Whereas Frege’s goal was to absorb the natural numbers, and hence part of mathematics, into logic, the modern perspective is to couple them in the opposite way: it is logic that is emergent!

Finally we come to Frege’s distinction between “a = a” and “a + b = b + a”, which he discusses in a few places including in On Sense and Reference (1892). He didn’t incorporate it directly into his logic or concept script, but he spent some time describing the distinction as a sort of metamathematical commentary. This has been the most recent and perhaps unexpected vindication of Frege’s priorities. Intuitionistic type theory indeed includes exactly the two kinds of equality Frege distinguished. One of them, dubbed “judgmental equality”, operates at the level of sense while the other, named “propositional equality”, which is a type, corresponds to reference. Having equality of sense gives you equality of reference automatically, but not vice versa. The exploration of these propositional equality types has led to the discovery of homotopy type theory and its infinite tower of equality types. Since equality is a type, there can be equalities between equalities and so on. This then turns out to generate an even more powerful theory for proving mathematical results.

5. Proof assistants: vindication of Frege’s concept script

Frege’s vision was for mathematicians to use logic and gap-free formal methods to strengthen the research they were already doing, i.e. the seeking of scientific truth. Nowhere is this goal more visibly realized than in the community projects that have grown up around various proof assistants. Two prominent examples are Mathematical Components23, which uses the Coq proof assistant, and Mathlib24 which uses the newer Lean proof assistant. There are mathematical communities around each of the other proof assistants as well, such as Isabelle, HOL Light, Agda, and so on. Some of these communities are growing quickly25, and I imagine new languages will come along every few years as well to stir the pot. The mathematical communities and their leadership are distinct from the teams that implement and support the proof assistant software. The goal is to formalize some body of mathematics, eventually all of it, using the proof assistant. The math libraries are therefore a combination of a software project and a mathematical project. We should equate the focus of these teams on the mathematical content itself, and not just the tools, with an alignment with Frege’s vision of the concept script as a mere microscope.

There are diverse public statements by mathematicians such as Vladimir Voevodsky, recipient of a Fields Medal in 2002, who expressed worry in 2015 about the scale of the mathematical literature and how this undermines the certainty of new results26:

“The world of mathematics is becoming very large, the complexity of mathematics is becoming very high, and there is a danger of an accumulation of mistakes,” Voevodsky said.

[…]In 1999 he discovered an error in a paper he had written seven years earlier.

Kevin Buzzard frames this same problem as a crisis of rigor27:

Buzzard believes that these kinds of problems [mistakes and unpublished proofs] undermine pure maths to such an extent that it’s slid into a crisis.

And Peter Scholze, recipient of a Fields Medal in 2018, explains how the formalization project he led went very smoothly, and also made a profound contribution to his understanding of the theory itself28:

I am excited to announce that the Experiment has verified the entire part of the argument that I was unsure about. I find it absolutely insane that interactive proof assistants are now at the level that within a very reasonable time span they can formally verify difficult original research. Congratulations to everyone involved in the formalization!!

What else did you learn?

Answer: What actually makes the proof work! When I wrote the blog post half a year ago, I did not understand why the argument worked, and why we had to move from the reals to a certain ring of arithmetic Laurent series. But during the formalization, a significant amount of convex geometry had to be formalized (in order to prove a well-known lemma known as Gordan’s lemma), and this made me realize that actually the key thing happening is a reduction from a non-convex problem over the reals to a convex problem over the integers.

All of these scientists developed a positive view towards the formalization of mathematics mid-career. The common reason is that they all wanted to keep doing mathematics successfully. They wanted to do the same work as before, but with more certainty. This is exactly what Frege was proposing. But on top of that, Scholze in particular articulated the additional benefit Frege highlighted, that when formalizing math “one must write down all intermediate steps, to let the full light of consciousness fall upon them”. The computer mediated the additional shared understanding of actual mathematics, by structuring the work required to build the theory, and by forbidding gaps.

It will help to tease out what parts of the mathematical agenda the computer is currently helping with, because then we can spot the area where the actual crisis has begun. To study this I used the Lean proof assistant myself. I proved the proposition we discussed above, is_algebra(M → ℝ)29. Lean has a small “trusted kernel” where the core logic is implemented, and this corresponds to Frege’s logic, albeit expanded into the more powerful logic of intuitionistic type theory. In addition to the kernel, the language allows proofs to be built up incrementally with tactics that advance the state of the proof by applying various transformations and lemmas. Sometimes it’s more intuitive to apply a tactic to the chain of steps that started with the assumptions, and sometimes you want to apply a tactic to transform the chain that leads to the goal. Eventually they will meet in the middle and form an unbroken chain. The software permits you to focus on one step at a time. It also enables you to designate one step as a possibly large sub-problem, which becomes the current lemma to prove. What the computer is offering among other things is a set of affordances to support a linear ordering of the work.

I browsed the library of theorems about smooth and topological manifolds, and the library of definitions around vector spaces, rings, and algebras. I saw how to create an algebra out of a carrier object plus some operations, plus proofs that the carrier object was closed under those operations. I will call this the “proof strategy”. Then I performed the work to enter all this data into my own source file. At any given moment I could choose a place to add a step to the proof, at which point I had to type something! Knowing what to type after you choose a location is a tough sub-problem that I want to highlight. In summary, to formalize a proof you must:

- Formalize all the definitions.

- Plan the strategy, i.e. the method of proof. In my case the strategy was to prove that the collection of smooth real-valued functions satisfied each of the half-dozen requirements to be an algebra.

- Perform many iterations of the small-scale tactical piece: select a rule or lemma from the library, and apply it somewhere on the frontier of the proof.

- Choose an order to perform the actions in 3.

The community manages the storage of definitions and existing theorems in the digital library (such as the Mathlib Github repository), which helps with 1. The mathematical content exists mainly in 2. Often an existing known proof is what you need to formalize, but in other situations you might have reason to prove the result with a different method in order to fit the logic being used. For example, some type theories do not offer classical logic such as the law of the excluded middle, requiring constructive proofs. Often these are not available in the literature. The computer helps with 3 and 4, and I want to come back and focus on 3 in a moment.

Lean’s tactics engine is one way to support 4. The whole paradigm of tactics is that you build up the proof from small commands. But other systems like Agda lack this explicitly incremental paradigm. Instead they offer interactive tools to probe the state of the proof, or leave figurative holes to come back to later. These contortions that the user went to are not saved with the file, however.

So what about 3? If you are in the middle of a proof, and you believe that elsewhere in the library is a lemma that the pointwise product of two smooth functions is smooth, how do you find it so that you can type its name? What if you don’t know whether that lemma is available or not? This portion of the task is not apparent in Frege’s description but turns out to dominate the work. This is also the least mathematical part of the process! And it is here where mathematicians began to envision a role for artificial intelligence. What if I was in the middle of this proof and I could ask the proof assistant to search for an appropriate lemma? It could use any combination of brute-force search through all the definitions in the library, or some naming hints, or even some patterns learned from a database of example proofs. All of these approaches are taken by a diverse collection of tactics. The most general-purpose tools are sometimes called “hammers” because of the name of an early paradigmatic example. The community is eager for new hammers to help with such searches. One recent example in Coq was worthy of publication30. The expertise required is quite orthogonal to the subject matter of smooth manifolds, and so it makes sense for a different sort of specialist to help tackle it.

But it turns out there is a bit of a trap here. We converted a mathematical problem that used to be tackled with pencil and paper into a semi-computerized process. One part of that process, the finding of lemmas, is a problem entirely created by the computerization! It turns out to be hard for people to convert back into a human-solvable problem. And so now we have phoned our friends in the AI department to help us solve it. Might an AI researcher look at formalized math and wonder if the computer can do all of it, and do it better than people?

6. The privilege to do math

For fear of obfuscating what I want to say about today’s crisis let me start by simply stating it: I think limiting the definition of “doers of mathematics” to people as soon as possible would be a healthy step. I think we should close ranks to defend this position because it is being attacked under the cloak of AI research. But I also think that computers are amazing tools and I have devoted my own career to making them smarter. Many mathematicians have the same positive view of computers, especially those in the formalization community that I have described. This makes it seem that I am trying to split hairs, and I worry that this appearance will make it even more difficult to mount a humanist defense against AI. My goal for the rest of this section is to convince you that:

- Some prominent AI researchers want to redefine mathematics to include computers as the doers, in the way others have done for the playing of chess and Go.

- Some mathematicians want to yield to this.

- Frege offers a vision for compartmentalizing the use of computers in math.

6.1. Quanta’s muddled report

In the 2020 Quanta Magazine article “How Close are Computers to Automating Mathematical Reasoning”31 we get a good status report on the redefinition of mathematics as non-human. Several researchers are quoted in the article, but their viewpoints do not gel into a single coherent narrative. The picture becomes much clearer if we examine each quote and ask “is this person focused on helping people do math, or helping computers do it?”

Michael Harris (a mathematician) wants people such as himself to do math and he worries that a proof assistant would make it harder: “By the time I’ve reframed my question into a form that could fit into this technology, I would have solved the problem myself.”

Kevin Buzzard (the mathematician and evangelist for formalizing mathematics we met earlier) wants computers to be mathematicians and claims that mainstream mathematicians want the same: “Computers have done amazing calculations for us, but they have never solved a hard problem on their own,” he said. “Until they do, mathematicians aren’t going to be buying into this stuff.” I want to especially note the circular salesmanship in this sentiment: we want computers to get better at doing math because we want to sell the project to mathematicians, presumably so that computers can continue to do more math for them.

Emily Riehl wants to learn to do math with a proof assistant and wants her students to learn too: “It’s not necessarily something you have to use all the time, and will never substitute for scribbling on a piece of paper,” she said, “but using a proof assistant has changed the way I think about writing proofs.”

Two computer scientists, Christian Szegedy (at Google) and Josef Urban (at the Czech Institute of Informatics, Robotics and Cybernetics) want to teach computers to do math without any human involvement:

Urban was partially inspired by Andrej Karpathy, who a few years ago trained a neural network to generate mathematical-looking nonsense that looked legitimate to non-experts. Urban didn’t want nonsense, though — he and his group instead designed their own tool to find new proofs after training on millions of theorems. Then they used the network to generate new conjectures and checked the validity of those conjectures using an ATP[automatic theorem prover] called E.

The network proposed more than 50,000 new formulas, though tens of thousands were duplicates. “It seems that we are not yet capable of proving the more interesting conjectures,” Urban said.

[Szegedy’s] group at Google Research recently described a way to use language models — which often use neural networks — to generate new proofs. After training the model to recognize a kind of treelike structure in theorems that are known to be true, they ran a kind of free-form experiment, simply asking the network to generate and prove a theorem without any further guidance. Of the thousands of generated conjectures, about 13% were both provable and new (meaning they didn’t duplicate other theorems in the database). The experiment, he said, suggests that the neural net could teach itself a kind of understanding of what a proof looks like.

“Neural networks are able to develop an artificial style of intuition,” Szegedy said.

We will come back to Szegedy and the idea of computers generating theorems shortly. Note however that these researchers are not extending proof assistants with hammers and the like. Instead they are digesting the existing human-crafted proofs and treating them as raw data to train neural networks that are similar to those that perform other text-based tasks such as translating text or performing automatic summarizations.

Getting back to the article, Timothy Gowers (a mathematician) says computers will literally replace mathematicians (without saying whether he thinks this is good):

mathematicians will enjoy a kind of golden age, “when mathematicians do all the fun parts and computers do all the boring parts. But I think it will last a very short time.”

Michael Harris has some pushback on this: “Even if computers understand, they don’t understand in a human way.”

6.2. Only people have meaning

Szegedy’s confusion can be traced in a way to a misreading of Frege. Here is Szegedy’s definition of mathematics:

Mathematics is the discipline of pure reasoning. Mathematical reasoning is not about mathematics per se, it is about reasoning in general.

This is taken from Szegedy’s 2020 article32 as cited by Harris33, who grapples in his public writing with the uses of AI in mathematics. Szegedy’s position erases literally everything that has value. Think again of Frege’s separation: there is logic, and there is mathematics. Logic and the concept script are methods for making airtight arguments while doing mathematics. Szegedy is taking the “doing mathematics” part and folding it back into the logic. There is only logic for Szegedy – “reasoning in general”. And so if the computer can learn to emit deductions automatically with a method that draws on human examples, then the computer is doing mathematics. After all, mathematics is not about mathematics per se!

I simply do not believe that the bare theorems themselves, or their proofs, carry any intrinsic value or meaning. After all, they are analytically entailed by the starting material, i.e. the definitions, axioms, and rules of logic. They do not themselves carry any information beyond that. There is a large space of facts that are entailed by these same starting conditions, and every point in this space carries, by itself, merely that information. Only by selecting one such result for a moment, for some reason, can we make one of them special and carry additional meaning. Meaning for us is inside us, tautologically. Therefore automatically enumerating theorems can add no meaning.

Is a computer playing chess when a user interacts with chess software? Only if the computer is also playing chess when it is playing both sides of the game by itself, like when training AlphaZero34. The only meaning of such a game stems from the fact that there are some people who set the computer to that task. The people behind the game, and their motives, have meaning, but the game does not stand by itself as a meaningful act. I can easily grant such a game a meaning, by a conscious act! But if I don’t, then nothing happens. The game cannot insist, it is not a source node for meaning.

So where is the idea coming from that the computer is indeed playing chess? I propose that the programmers of the computer are asking us to grant it that, as they have. Who benefits if we agree, and who suffers a negative consequence? And who benefits if we disagree? I’m insisting that we focus only on people, so we should focus on people when we try to figure out why we’re being asked to call the computer a person.

Let me say this one final way. When Szegedy’s team’s computer emits some theorems, how will they evaluate the results? How long will they stare at the meaningless (to them) output before they copy and paste it into an email to a mathematician? They will have to bring these theorems to human mathematicians to interpret them and evaluate them. There is no other notion of interpretation. There is no audience besides the audience of mathematicians. When a willing mathematician identifies some such result as interesting and tells Nature magazine about it35, that person will perhaps transfer some of the fame of mathematics onto the programmers and their computer. The whole process conserves the value the mathematician was already bringing.

And when these programmers need to build their AI, how will they do it? We know how because it has already been done. The programmers will copy the data files from a public repository of HOL Light, Coq or Lean proofs, and encode them as training examples for the computer. Again, the computer can only perform analytic trivialities, and so mathematicians need to both create the input and evaluate the output.

Will mathematicians cooperate? Should they? What could we even do? My only suggestion at the moment is to choose a restricted license file to attach to the source code repositories of Mathlib and the other libraries. Currently Mathlib uses the Apache 2.0 license, which is a very permissive license in common use. It even allows commercial uses.

What will happen in five years after ten very hard problems are solved through a collaboration with AI? Who will explain to society that the humans are still doing all the meaning-making? And when we try to explain, will the programmers cooperate?

6.3. Good uses of computers

So what then are some value-enhancing uses of computers? Frege showed us one: use computers to implement the concept script, to help formalize mathematics. Inside the formalization software are additional affordances such as tactics, which constitute entirely new use cases for the computer that also help us bring meaning into the world.

Other promising use cases are being invented daily. One family of ideas is to make better search engines for mathematical literature, or for specific theorems. MathFoldr36 aims to use wikis such as the nLab37 as data sets to learn how to add metadata to mathematical texts, enhancing search indexes. Their stated goal is suitably humanistic: “MathFoldr will provide search and literature curation tools that will make mathematics more accessible, with the ultimate goal of transforming the way mathematics is created and navigated”.

FAbstracts38 aims to build a digital library of formalized mathematics, including the statements of not-yet-formalized results. But their vision statement is as muddled as the Quanta article, having as goals both the worrisome “machine learning in math” as well as the more human-centered “tools for exploration such as a Google Earth for mathematics, providing an intuitive visual map of the entire world of mathematics”.

The mathematician William Thurston said “Mathematics is not about numbers, equations, computations, or algorithms: it is about understanding.”39. Doing mathematics makes changes to us, to our minds. Proving theorems with a computer brings a strikingly similar experience to proving them on paper. That is because the meaning of the act is the same.

References

-

Frege, Gottlob, Begriffsschrift, p. iii, from The Frege Reader, Micheal Beaney (ed.), Blackwell 1997 ↩︎

-

ibid., p. iv ↩︎

-

ibid., p. 8 ↩︎

-

Read more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Square_of_opposition ↩︎

-

Begriffsschrift, p. 24 ↩︎

-

ibid., p. iii ↩︎

-

ibid., p. iv ↩︎

-

ibid., p. 3 ↩︎

-

ibid., p. vi ↩︎

-

Frege, Gottlob, Foundations of Arithmetic, p. ii, from The Frege Reader, Micheal Beaney (ed.), Blackwell 1997 ↩︎

-

Frege, Gottlob, Basic Laws of Arithmetic, p. vii, from The Frege Reader, Micheal Beaney (ed.), Blackwell 1997 ↩︎

-

https://www.imo.universite-paris-saclay.fr/~pmassot/files/exposition/why_formalize.pdf ↩︎

-

Basic Laws of Arithmetic, p. viii ↩︎

-

Daston, Lorraine. “Calculation and the Division of Labor, 1750-1950.” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 62.Spring (2018): 9-30. ↩︎

-

On Euclidean Geometry, p. 183, from The Frege Reader, Micheal Beaney (ed.), Blackwell 1997 ↩︎

-

ibid., p. 184 ↩︎

-

Megill, Norman D. and Wheeler, David A. (2019) Metamath: A Computer Language for Mathematical Proofs, Lulu Press. http://us.metamath.org/downloads/metamath.pdf ↩︎

-

Simpson, Stephen G. (2009), Subsystems of second-order arithmetic, Perspectives in Logic (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

-

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/type-theory-intuitionistic/ ↩︎

-

https://leanprover-community.github.io/mathlib_stats.html ↩︎

-

https://www.quantamagazine.org/univalent-foundations-redefines-mathematics-20150519/; links to https://www.ias.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/letter-2014-summer.pdf ↩︎

-

https://xenaproject.wordpress.com/2021/06/05/half-a-year-of-the-liquid-tensor-experiment-amazing-developments/ ↩︎

-

https://github.com/glangmead/geometry/blob/ab8cbeab722eb3df8d77885f812af8063b1f5906/src/algebra_of_smooth_functions.lean ↩︎

-

Czajka, Ł., Kaliszyk, C. Hammer for Coq: Automation for Dependent Type Theory. J Autom Reasoning 61, 423–453 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10817-018-9458-4 ↩︎

-

https://www.quantamagazine.org/how-close-are-computers-to-automating-mathematical-reasoning-20200827/ ↩︎

-

Szegedy C. (2020) A Promising Path Towards Autoformalization and General Artificial Intelligence. In: Benzmüller C., Miller B. (eds) Intelligent Computer Mathematics. CICM 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12236. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53518-6_1 ↩︎

-

https://siliconreckoner.substack.com/p/intelligent-computer-mathematics ↩︎

-

Silver, David, et al. “Mastering chess and shogi by self-play with a general reinforcement learning algorithm.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.01815 (2017). ↩︎

-

https://topos.site/blog/2021/07/introducing-the-mathfoldr-project/ ↩︎

-

Cook, Mariana. Mathematicians: An Outer View of the Inner World. Princeton University Press, 2009, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jc8h2. ↩︎